SedimentPPCPs (µg/kg dry weight)

|

MusselsPPCPs (µg/kg wet weight)

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

North |

|

| South |

What are they?

Pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) include all prescription, over-the-counter, and medications made for humans and animals, such as antibiotics, supplements, growth hormones, and birth control hormones (pharmaceuticals), as well as cosmetics, soaps, lotions, and hair and dental care products (personal care products). The PPCPs detected in Pollution Tracker samples are summarized in Table 1.

Which ones were detected?

In Phase 1 (2015-2017), PPCP analysis included only 12 compounds, and only one compound was detected (triclocarban). In Phase 2 (2018-2020), up to 90 PPCPs were analyzed in many of the samples (47 sediment samples, 31 mussel samples).

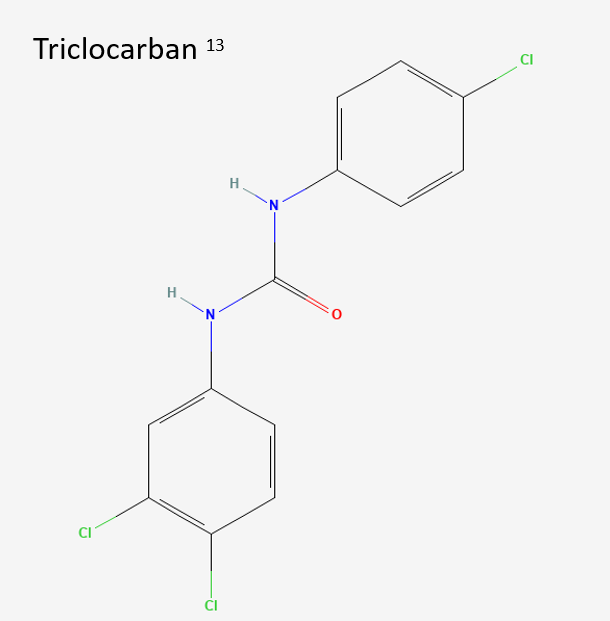

Table 1. PPCPs detected in Phase 2 Pollution Tracker samples.

How do they get into the ocean?

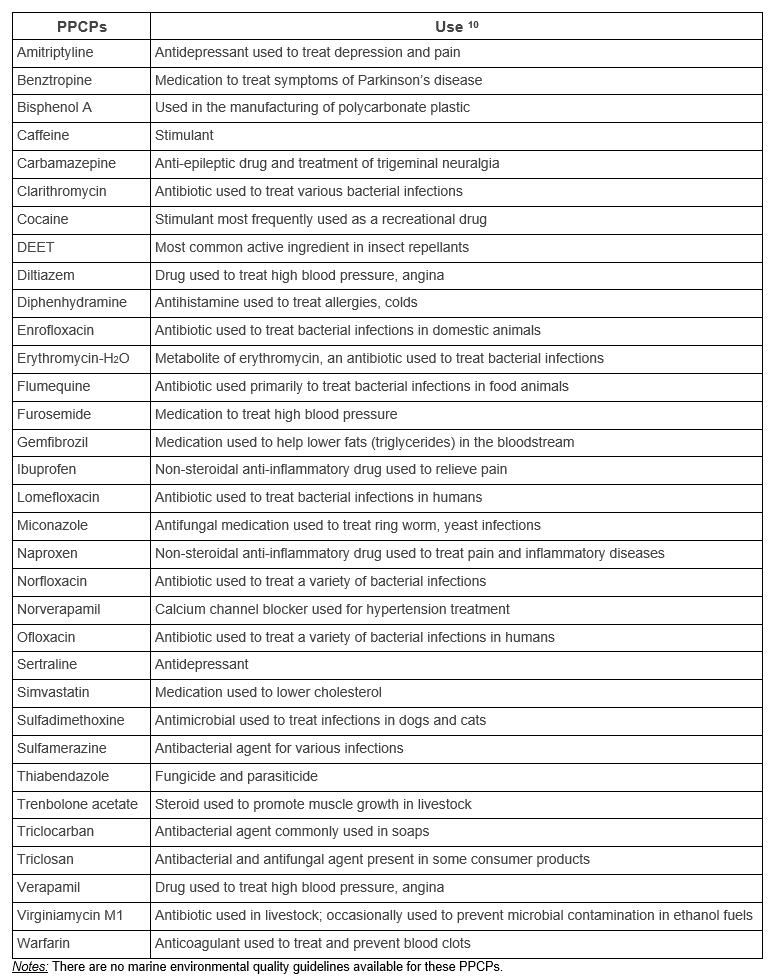

PPCPs largely enter the marine environment via wastewaters from areas of urbanization and animal production. Pharmaceuticals are also used at aquaculture facilities to prevent and treat outbreaks of disease and sea lice.1 While some PPCPs degrade quickly, they are considered pseudo-persistent in the environment due to continual inputs.1 Others, such as the antimicrobial agents triclosan and triclocarban persist in the environment and are known to accumulate in aquatic organisms, including algae, worms, fish, and dolphins.2

Are they a problem?

PPCPs can have a variety of toxic effects in biota, and the potential effects of many PPCPs are currently unknown.

FACT: The effects of PPCPs on non-target organisms in the environment may be so subtle that they are undetectable, but these effects are potentially cumulative and may be significant over time.3

Pharmaceuticals of special concern in the environment are those used for chemotherapy (antineoplastics), birth control and growth hormones (endocrine disruptors), and antibiotics.1 Antimicrobial agents are considered particularly problematic components of personal care products.1 Adverse effects on non-target organisms following laboratory exposure to pharmaceuticals include disruption of hormones and enzymes (molecules that speed up chemical reactions in the body) in fish, toxicity and disruption of community structure in algae, and changes in sex-ratios in amphipod populations.1

The antimicrobial agents triclosan and triclocarban are widely accepted as toxic to aquatic organisms and have been found to be more effective in inhibiting or killing algae, crustaceans, and fish than in killing their target (microbes).2 However, their potential effects on human health are less well understood, and Health Canada considers triclosan and triclocarban safe for humans at current levels of exposure.4,5

Bisphenol A (BPA), a compound used to produce epoxy resins and polycarbonate plastics, is a known endocrine disruptor and is also acutely toxic to many marine organisms. Environment Canada and Health Canada assessed bisphenol A and concluded that it can have immediate and/or long-term harmful effects on the environment and biological diversity. 6

Although little is known about the fate and effects of many of the PPCPs detected in Pollution Tracker samples, their continuous release into the environment, even at low concentrations, can potentially impact aquatic organisms over the long term.1

What is being done?

Marine environmental quality guidelines are not available for PPCPs in Canada. Freshwater guidelines are currently available for carbamazepine 9, triclosan 9 and bisphenol A.6 Environment and Climate Change Canada is currently undertaking a risk assessment process for triclosan, with the objective of reducing the quantity of triclosan released to the aquatic environment. 5

In 2016, the United States Food and Drug Administration banned the use of triclosan, triclocarban, and 17 other chemicals in over-the-counter personal care products. The 2016 Florence Statement on triclosan and triclocarban has been signed by more than 200 international scientists and medical professionals, with the aim of sharing current scientific research motivating broader consideration of the long-term impacts of antimicrobial use. 7

In 2010, Environment and Climate Change Canada concluded that bisphenol A poses a risk to the environment and human health, and it was added to the List of Toxic Substances in Schedule 1 of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999.6 Subsequently, a Pollution Prevention Planning Notice for industrial facilities that use or manufacture bisphenol A was issued in 2012, and an Environmental Performance Agreement was established with 13 paper recycling companies in 2013 to limit environmental releases and impacts of BPA.12

What can you do?

As individuals and organizations, we can:

- Learn more about PPCPs and other contaminants of concern using the resource links below.

- Recycle and dispose of waste responsibly and according to local guidelines. For example, pharmaceuticals that have expired or are no longer being used should be taken to a pharmacy for disposal.

- Avoid using products that contain PPCPs known or suspected to cause toxicity in either humans or the environment (e.g., triclosan in soaps and toothpaste).

More information?

1 Garrett C and PS Ross. 2010. Recovering Resident Killer Whales: A guide to contaminant sources, mitigation, and regulations in British Columbia. Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2894.

2 Halden R. 2014. On the need and speed of regulating triclosan and triclocarban in the United States. Environmental Science & Technology 48: 3603-3611.

3 Daughton CG and Terns TA. 1999. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the environment: agents of subtle change. Environmental Health Perspectives 107: 907-938.

4 Health Canada. 2016. Triclosan. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/chemicals-product-safety/triclosan.html

5 Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) and Health Canada. 2016. Risk management approach for phenol, 5-chloro-2-(2,4-dichlorophenoxy) – Triclosan. Available at: http://www.ec.gc.ca/ese-ees/default.asp?lang=en&n=371a2f3c-1

6 Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) and Health Canada. 2018. Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 Federal Environmental Quality Guidelines. Bisphenol A. Available at: Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 Federal Environmental Quality Guidelines Bisphenol A – Canada.ca

7 Halden RU, Lindeman AE, Aiello AE et al. 2017. The Florence Statement on triclosan and triclocarban. Environmental Health Perspectives. 125 (6). Available at: https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/EHP1788/

8 Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). 2017. Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999. Draft Federal Environmental Quality Guidelines. Triclosan. Available at: https://www.ec.gc.ca/ese-ees/F6CF7AA4-1403-4ED1-8DE8-0B42BC1AA852/Triclosan%20Factsheet_En.pdf.

9 Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME). 2018. Canadian Water Quality Guidelines for the Protection of Aquatic Life. Carbamazepine. Available at: https://ccme.ca/en/res/carbamazepine-en-canadian-water-quality-guidelines-for-the-protection-of-aquatic-life.pdf

10 Health Canada. 2021. Drug Product Data Database online query. Available at: Drug Product Database online query (canada.ca)

11 PubChem. 2022. Compound Summary: Triclocarban. Available at: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Triclocarban

12 Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). 2022. Bisphenol A in industrial effluents: pollution prevention planning notice. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/pollution-prevention/planning-notices/performance-results/bisphenol-a-industrial-effluents-overview.html.

13 PubChem Identifier: CID 7547 URL: Triclocarban | C13H9Cl3N2O – PubChem (nih.gov)